Continued from Part 1...

After lunch at Dairy Queen, Susan and I returned to our hotel rooms for a siesta before we went to Fort Bayard Historic Site and the Bataan Memorial exhibit. We had tried to find the correct parking lot for the Bataan Death March Memorial a couple of days ago when we did the Dragonfly Trail; however, when we got to the parking lot it was late in the day and we weren't positive it was the right place. Today, we found that we had been in the correct parking lot.

After a very short walk from the parking lot, we came to the Bataan Death March Memorial. This Bataan incident began in December 1941, in Bataan, Philippines.

|

| "Remembering Bataan: Honoring our Heroes," fall 2008- spring 2010. Art was done by the Youth Mural Program. |

A commemorative sign on the gate states:

"Within hours of their December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese military began its assault on the American outposts in the Philippines. Manila was a perfect Japanese resupply point for their planned conquest of the southern Pacific. On December 22, 1941, 43,000 men of the Imperial Japanese 14th Army went ashore on the main island of Luzon.

"General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, ordered American troops to retreat to the southern Bataan peninsula. Troops in Bataan resisted the Japanese until April 9, 1942, when 22,000 American and 54,000 Filipino soldiers surrendered. The Japanese military followed the Bushido code, in which surrender was shameful and death was preferrable. Prisoners started out from Mariveles on April 10, and were force-marched north 65 miles with no food or water to the San Fernando railhead. At the San Fernando railhead, as many as 100 prisoners were stuffed into sweltering (16' long x 8' wide x 6' high) box cars for the 25-mile trip to Capas, then they walked nine miles to Camp O'Donnell."

Other signs at the memorial added to the story:

"When the over 70,000 soldiers were surrendered, there were over twice as many prisoners as were expected by the Japanese. The prisoners of war were in terrible shape - sick, wounded and malnourished. The Japanese had to get them out of the way as soon as possible. That meant moving them 60 miles in sweltering heat and 100% humidity on what became the infamous 'Death March.'"

"POW Camps: The prisoners of war (POWs), weak, starving, thirsty and sick arrived at their first and for many their last POW camp, Camp O'Donnell, nicknamed 'Camp O'Death.' Around 50 American prisoners would die every day. There they received very little food and water but much brutality and torture along with many diseases like beriberi and pellagra to go along with the malaria and dysentery which they already had."

"Hell Ships: The Empire of Japan required great numbers of workers and huge quantities of raw materials in order to wage war against the Allies. In May 1942, the Japanese began transferring its captured POWs by sea in cargo-laden ships. The holds were floating dungeons, where inmates were denied air, space, light, bathroom facilities, and adequate food and water - especially water.

"Thirst and heat claimed many lives, as did summary executions and beatings, yet the vast majority of deaths came as a result of so-called 'friendly fire' from U.S. Allied naval ships, submarines, and aircraft."

"After: After returning home with battle fatigue a.k.a. shell shock, now PTSD, they had difficulties reintegrating into family life, with their depression, claustrophobia, nightmares, flashbacks, alcoholism, and breakdowns. Some had marital difficulties, some committed suicide, and others simply carried on while not sharing their stories. BUT, they were paid $1.00 a day for each day they were a prisoner."

|

| This Bataan Memorial honors New Mexico's fallen soldiers. |

When we finished reading all the history here, we walked over to the Forgotten Veterans Memorial. We walked the path through the compound.

|

| The Forgotten Veterans Memorial overlooks Fort Bayard. |

In the pavilion here, there is a sculpture of a table for the forgotten veteran in a restaurant. It was very moving. With the afternoon lighting in the pavilion, it was hard to get a picture that would do it justice.

From the Forgotten Veterans Memorial, we walked back through the parking lot, across the road, and entered Fort Bayard. This 468-acre fort is not only historically rich; it is also abundant in natural beauty. Visitors can choose from a variety of programs and special events which include re-enactments, presentations, and annual celebrations. Guided tours are given throughout the year and pass through the stately officers' quarters or "Doctors' Row," which faces the parade ground.

Our impression is that Fort Bayard has been left to decay. It's like a ghost town. There have been talks over the years to restore parts of the Fort, but nothing has ever come of them. The way it looks now, it would take a whole lot of money to bring these buildings up to current standards!

|

| This is the first Officer's Quarter building we saw. It's in very bad shape. |

|

| Guided tours start here. I heard there is a small museum inside with limited hours. |

|

| What the original Officer's Quarters looked like. |

(*Heliograph: a mirror mounted on a tripod or post on top of a mountain, which used the sun's rays to send messages in Morse Code across long distances. During the Geronimo Campaign of 1886, 24 heliograph stations were used, spanning from southern Arizona to southwestern New Mexico. Morse Code was flashed by mirrors from mountaintop to mountaintop across great distances. In one instance, a message traveled 700 miles in four hours!! The heliograph system served to send messages from areas without telegraphs and where telegraph lines had been severed by the Apaches. This was an extremely effective means of communication during the Geronimo Campaign.)

|

| Second Lieutenant John J. Pershing. |

In 1886, Second Lieutenant John J. Pershing of World War I fame, had his first posting at Fort Bayard with the 6th Cavalry, just two weeks after Geronimo's surrender. He was assigned the task of establishing heliograph stations from Fort Bayard to Signal Peak, and then on to Fort Stanton.

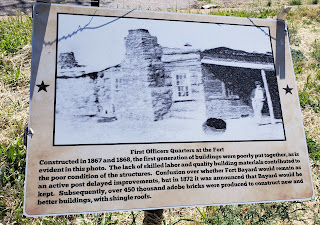

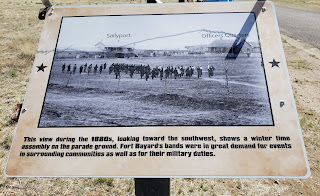

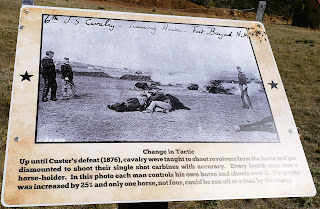

The following historical signs show what life was like in the mid-to-late 1800s.

|

|

| The parade ground was used for many activities. |

|

| The fate of the Apache scouts. |

|

| An interesting lesson was learned. |

From 1866 until August 28, 1899, Fort Bayard had been a military post. That came to an end in 1899 when the Army Medical Corps took over the property. the War Department authorized Surgeon General of the Army, General George M. Sternberg, to establish a hospital at Fort Bayard for use as a military sanitorium, the first of its kind. His strong interest in the treatment of tuberculosis was instrumental in retaining the fort.

- Doctors Row houses were constructed from 1906-1911 as homes for the Army doctors assigned to the Fort Bayard Tuberculosis Hospital.

- Nurses Quarters opened in 1910.

- A new water tank was erected.

- A glass solarium was constructed within the first few years of the tuberculosis era.

- Barracks were replaced with "ambulatory wards" for those patients who were not confined to constant bed rest.

- Trees and landscaping were added to the parade ground. Picnics, band concerts, boxing matches, and leisurely strolls were all part of daily life revolving around the parade ground. In later years, a baseball field was added.

- A Hospital Administration Building was added in the final years of the facility's time as an Army Hospital.

- A wide assortment of patient wards and other facilities were added.

- 1889 - Army surgeon Major Daniel M. Appel. He found that open air at high elevations was beneficial to his patients, believing that the resulting increase in red blood cells contributed to health.

- 1904-1917 - Commanding Officer Army surgeon Dr. George E. Bushnell believed convalescing soldiers recovered more quickly at high elevations, with clean air, abundant sunshine, and low humidity. In addition, wholesome foods from the post's gardens, dairy herds, and poultry and livestock, contributed to the patients' welfare. Major Bushnell joined Appel in pioneering research and treatment of tuberculosis.

- 1900 - Dita Kinney, contract nurse, arrived at Ft. Bayard U.S. Army Hospital to serve as Chief Nurse. In 1901, she became the first director of the Army Nurse Corps.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please let me know what you think, your experiences, and constructive criticism to make this blog stronger.